No doubt we have all experienced the anticipation; waiting patiently, tapping a red pen, possibly even nervously biting our nails, eager to tick or cross our answers to that test. Whether it’s the weekly trivia quiz or a Year 5 spelling exam, all of us have experienced the desire to find out whether or not our responses were accurate.

What happens though when they’re not? Commonly enough, you may have heard the phrase, “It’s okay, just learn from your mistakes.” Indeed, many articles have discussed the need to make mistakes in order to be successful. Famously, Bill Gates’ first enterprise with future Microsoft partner Paul Allen, was a terrible failure. When selling Traf-O-Data the pair grossly underestimated the benefit of market research which in turn rendered the software useless. It was learning from this failure however, that guaranteed the success of their next big development, Microsoft.

So what does this mean for the classroom? Well, creating a culture where mistakes are acceptable is one thing but ensuring that students are then primed to learn from their mistakes is a much more complex task. Here are a series of steps that you can take to ensure that when mistakes are made they do indeed facilitate learning:

Set Challenges

Have you ever attended a gym class or seminar where you’ve come away thinking you didn’t challenge yourself; not because you thought one extra push-up was just too much, but because the tasks were far too easily achievable? This disconnect in the classroom is, as John Hattie suggests, the result of “boredom” and “lack of appropriate challenge.” In such an environment it is no wonder then, why risks aren’t taken – nothing can go wrong!

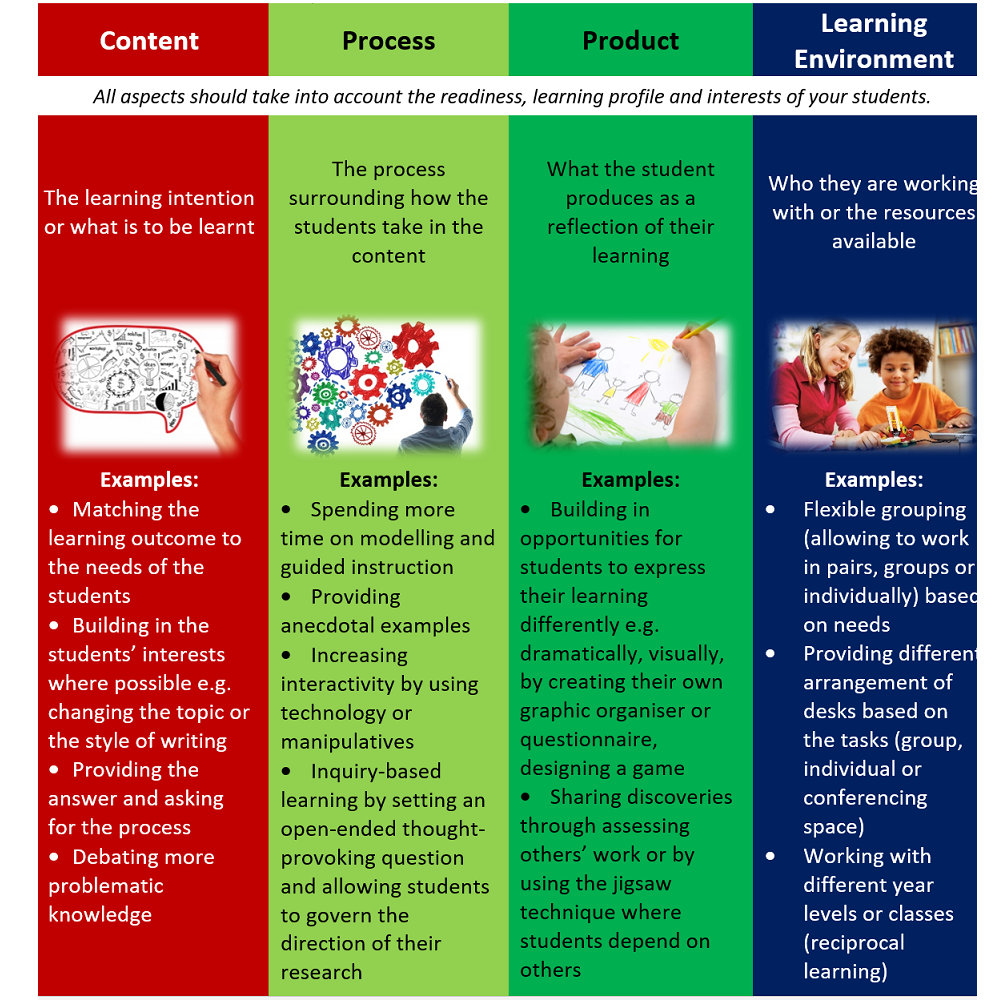

Some subjects lend themselves to more risk taking through greater opportunities for open-ended tasks and differentiated learning. Most importantly though, challenges can also come in forms other than changing the content of the lesson; changing the process, product or learning environment can also increase the challenge of a task and thus allow students to step slightly outside their zone of proximal development. Carol Ann Tomlinson, known for her monumental research into differentiation, advocates for striking a balance between challenge and achievability to ensure every student learns “as deeply as possible and as quickly as possible”.

Differentiating to Set Challenges

Changing from Failure to Effort: A Growth Mindset

Fear of failure is crippling. After all, the phrase, “you’re a failure” doesn’t tend to instil confidence in anyone, let alone our students. However, if we are going to strive for an environment where risks are taken, ‘failure’ is a natural part of the process. In order to ensure that students take risks we need to change the focus from correcting failures to encouraging persistent effort. Rewarding bold choices and celebrating the process taken after a mistake, changes the emphasis from the result to the possibility for growth. Similarly, changing the discourse from ‘wrong’ to ‘just not right, yet’ conveys a powerful message of opportunity in the classroom. As Carol Dweck highlights in her TED talk, reminding students that they have mastered things they once got ‘wrong’, allows them to understand their place on the learning curve and stresses that through ongoing effort and persistence they will eventually achieve. Giving valuable feedback that shows students how they can grow or fuels the idea that risks are opportunity!

Make Retakes the Norm

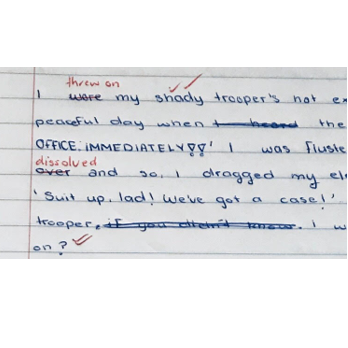

Along the same vein, allowing and encouraging retakes is a fantastic way to increase risk taking. Knowing that you can try and try again emphasises the need for different strategies instead of putting the importance on the outcome. A great way to facilitate this in writing is to always set an editing task. Encouraging students to write freely, concentrating mainly on structure before going back to edit for flourishing details not only compartmentalises the process, making it more manageable, but also allows for risk taking. Rewarding the students who goes back and change a basic verb to a more sophisticated word increases the likelihood that they will take a risk with less familiar vocabulary.

Additionally, giving jeopardy-style activities, where the answer is provided but the students must work out different strategies to achieve this outcome, completely reverses the usual emphasis. In this case, trial and error is a must because there may be more than one solution.

Model Risk Taking

We’ve all had – or been – the teacher that makes a mistake on the board. Often, their response is “I did that to make sure you were paying attention”. Teachers constantly grapple with the balance between being considered knowledgeable enough to teach others and teaching their students that no-one is perfect. However acknowledging our own short-comings may actually be one of the most powerful tools we can give our students.

According to Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, children learn from observations of the people around them. Most importantly, once a child chooses to experiment with the modelled behaviour, “if the consequences are rewarding, the child is likely to continue performing the behaviour.” Therefore, modelling risk taking and a growth mindset after mistakes can increase the likelihood your students will take risks themselves. However, students must also be rewarded for their efforts to ensure ongoing perseverance. Emphasising the effort, small gains and steps for improvement rather than a perfect outcome facilitates ongoing risk taking and life-long learning.

Ensuring that learning results from making mistakes is a complicated process but is essential in today’s educational environment. Setting adequate challenges, changing the discourse from ‘failure’ to ‘not yet’, always allowing for and encouraging retakes and not being afraid to model risk taking ourselves, are just some of the ways to promote risk taking in the classroom. For further information on how to achieve this, I strongly advise reading ‘The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners’ by Carol Ann Thomlinson or watching Carol Dweck’s presentation on ‘The power of believing that you can improve’. But most importantly, first we must be willing to take on the risk to make a small change ourselves in order to promote greater risk taking in our students.

Good luck!

How do you encourage risk taking in your classroom? We would love to hear from you!

About the author

Ashleigh Underwood is a Western Sydney based, Primary Teacher who currently teaches Year 6. Ashleigh is an advocate for student wellbeing and creating creative and authentic learning experiences. As well as being a qualified teacher, Ashleigh also has her Bachelor degree in Psychology (Honours).